Last week we got to an exciting point in the project, with a visit to our Project Partners, The National Archives at their site in Kew. We, the Principal Investigator, Dr Jennifer Aston and Senior Research Assistant, Dr Diane Ranyard, spent 5 days exploring the archives.

So why were we there?

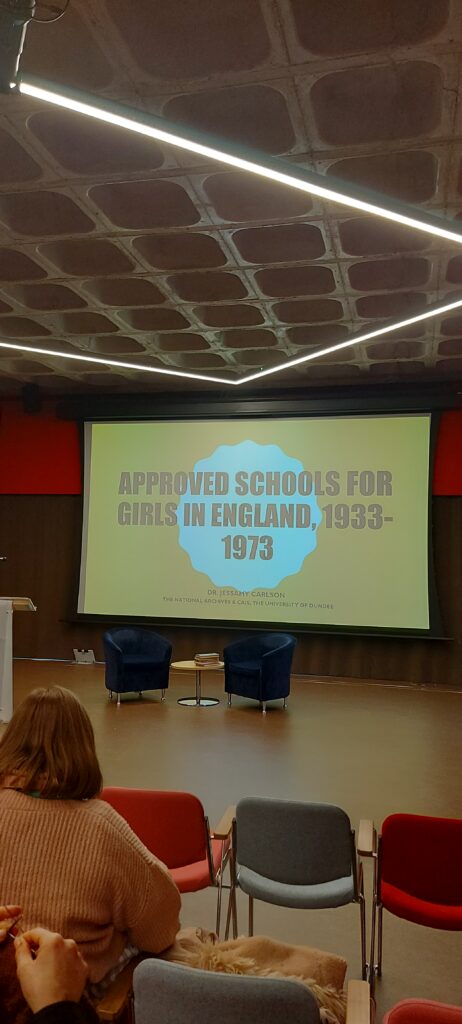

Our trip was a welcome opportunity to catch up with Dr Jessamy Carlson, the Family and Local History Engagement Lead at The National Archives who is on the project’s Steering Committee. While we were there, we were fortunate to be able to attend Jessamy’s book launch that was held at The National Archives, for her book Approved Schools for Girls in England, 1933-1973 (see image below). However, our main aim for the visit was to create digital images of the J 77 Court for Divorce and Matrimonial Cause files in our research sample, which haven’t yet been digitised. As we’ve discussed in a previous blog post, as well as forming the basis of our project, the J 77 Divorce Records are a rich source of information, particularly for genealogists and family historians who want to find out more about their ancestors.

What did we do?

A key part of our project is the creation of an interrelational database in which we are recording key information from the J 77 divorce case files. This includes important data from the case itself and genealogical information about the people involved (petitioners, respondents, co-respondents, judges, solicitors, barristers, clerks, etc.). Across the period we’re looking at (1857-1923) approximately 67,000 individual divorce case files survive. We initially selected a sample of 1,000 cases, though this has already expanded as we discover cases linked to our original 1,000 files. As we outlined in a previous blog post every case file for the years between 1858-1918 have been digitised and are easily available on Ancestry (charges apply) or they can be viewed in person for free at TNA with a Readers Ticket. If you want to see divorce case files from 1919 onwards, you have to book a trip at The National Archives, Kew to view the original documents. Roughly 70% of our sample cases have already been digitised, which left us with 300 cases dating from 1919-1923 to photograph during our trip.

How are the J 77 files stored and organised?

The J 77 divorce records are stored in boxes, and within each box are approximately 25-30 case files dependent on the thickness of the individual files, which can range from 3 to 100+ pages (see images below). Each file and box have a reference number that, when combined, creates a unique reference for each case, which is then used in the Discovery Catalogue. For example, the case file for Jane and Henry Alexander Mawson has the reference J 77/1825/6916 on the Discovery Catalogue. The first numbers after the J 77 prefix are the box number, and you can see the box number 1825 on the image below. The second set of numbers are the case file number, in this instance 6916 (you can see this case file in the second image below at the top of the pile).

As an aside, in this case from 1921, Jane Mawson successfully petitioned for a divorce using Poor Person’s Provision (legal aid) on the grounds of her husband Henry Alexander having committed bigamous adultery. Within the case file alongside the petition, certificate showing Jane had been awarded Poor Person’s Provision, the decree nisi and decree absolute forms, are two marriage certificates. One for Jane and Henry’s marriage in 1912 and another for the bigamous marriage in 1919 between Henry (going by his second name Alexander) and a woman called Martha Alice Beech.

The three hundred case files that we were creating digital images of were spread across 300 boxes. As we were looking at multiple boxes within a series we could do bulk orders of 40 boxes per day per person. Thanks to the hard work of the archivists at The National Archives, these were ready for us each day on trolleys (see image above) in the bulk order space at the archives. We had a camera and a stand, so our days were filled with finding the correct case files within the boxes and taking photographs of every page of the case files that are in our sample. Although much of the evidence presented to the Divorce Court has been removed from the files, we did find many unexpected items including photographs, private investigator reports, wedding day mementos and even Bibles!

What else were we looking at?

We’ve also been working on tracking repeat applications to the Divorce Court. As part of that research while we were at The National Archives, we’ve also taken digital images of a further 200 J 77 divorce case files from 1919-1937 for cases heard in the Divorce Court that involved the husbands, wives, co-respondents or named women in our original sample of 1000 cases from 1857-1923. We’ll talk more about repeat applications to the Divorce Court in an upcoming blog, and an upcoming chapter in a Research Handbook on Gender, Law and History (due for publication in summer 2026). For now, though, it’s safe to say that some people must have almost been on first name terms with the Judge Ordinary. Harry Kent for example, appeared in three cases, two as a defendant, and one as a co-respondent; more on him to follow! To do this it’s taken a lot of planning before we arrived, and after our visit we’ve been busy sorting, formatting and labelling our images so they’re easy to use when we enter the data from them into our database. We look forward to sharing some of the amazing discoveries we made last week, very soon.

Make sure to follow us on Blue Sky, Instagram, Threads, or Facebook where we’ll regularly post news about the project, and links to the blogs on the projects website.